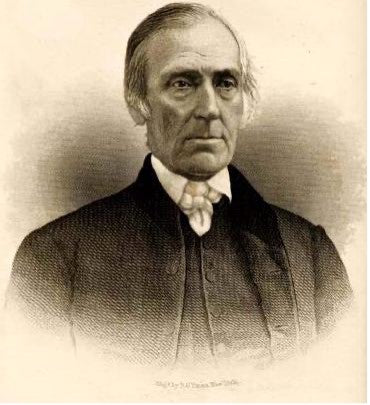

The President of the Underground Railroad

Often referred to as the President of the Underground Railroad, Levi Coffin’s profound conviction and efforts would help to alter the cultural views of slavery and assist with the assimilation of freedmen into American society. The Underground Railroad (UGRR) is one of the most iconic and mysterious historical organizations chronicled in American history. Caught somewhere between legend and fact, the history of this institution has become shrouded in personal accounts, fiction, and nonfiction. Because the existence of the Underground Railroad was founded in secrecy, records were not kept intentionally and many of the facts that have been derived from this period have been verified through fact comparisons in literature such Coffin’s personal biography and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As well as being locked in secrecy, the railroad was also not a uniform system or a formal structure. Like competing lines of the coal and iron version, the UGRR operating in the East did not have knowledge of the UGRR in the West. This disjointed operation allowed for better secrecy but confused historical viewpoints. It would also be safe to assume that many of the individuals who participated in the functioning of the Underground Railroad have been lost to history or have become elements of myth. But of the many accounts and biographies that have survived, Levi Coffin’s involvement in the Underground Railroad is one of the more well known, as it is mentioned in several notable documents and books.(1) Coffin assisted between 2,000 and 3,000 slaves find freedom. Although Coffin’s effects on the Underground Railroad were incredible, his efforts to assimilate newly freedmen into American society are often overlooked.

Born in the Southern United States, Coffin was exposed to slavery from an early age. As a Quaker, Coffin was indoctrinated with an opposition to slavery during childhood. Coffin was born outside New Garden in Guilford County, North Carolina on October 28, 1798, where he was raised as a farmer among a community of Quakers.(2) Coffin’s family and community were influenced by the teachings of John Woolman who was a staunch believer that slavery was not compatible with Quaker beliefs, and wrote several books and essays which advocated the emancipation of slaves.(3) It is believed that Coffin’s parents most likely met Woolman in 1767. This meeting was believed to have taken place during Quaker meetings near their New Garden home. Quakers who were non-slaveholding families met consistently discussing the problem of slavery and abolitionist ideology. During these meetings, Coffin would learn to detest slavery and perhaps learned how and possibly assisted his cousin Vestal Coffin, with helping slaves escape North Carolina. Vestel Coffin was one of the earliest known Quakers to assist slaves, beginning as early as 1819.(4) Levi and Vestal formed a school for slaves to study the Bible and Christianity, but because of too much interest from slaves the slave owners refused to allow their slaves further attendance.

While working on his father’s farm, Coffin frequently encountered slaves throughout his childhood and sympathized with their condition. By his own account, Coffin became an abolitionist by the age of seven. Coffin asked a slave who was working on a chain gang why he was bound.(5) The man told Coffin that it was to prevent him from escaping and returning to his wife and children. This particular incident seemed to disturb Coffin deeply and he related how the fear of his own father being taken away frightened him.(6) Being a devout Quaker, Coffin undoubtedly knew of the persecution that Quakers had endured early in the New World and in the old country. This fear of persecution and moral position of slavery would be a driving force for Coffin’s abolition.

Coffin, by the age of fifteen, was assisting escaping slaves by taking food and clothing to those hiding on his parent’s farm.(7) As the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 became increasingly enforced in the southern states, the Coffin family adopted a greater secrecy when providing assistance to runaway slaves. Living in North Carolina and assisting slaves was a dangerous undertaking and Coffin would learn to be secretive. Coffin’s early exposure to the dealings of the Underground Railroad would provide him with his experience to assist slaves in the future.

During these years, Levi Coffin became convicted to his Quaker beliefs regarding slavery and morality. Societal scrutiny of the abolitionist movement worsened with the passage of the 1804 Black Laws.(8) These laws began in Ohio but were adopted by most southern states and they diminished the mobility of free blacks and required them to prove their freedom through documentation. The codes further tried to limit individuals from helping slaves by imposing fines. By the early 1820s, Quakers in North Carolina were openly suspected and persecuted for assisting runaway slaves.(9) The Quaker abolitionist point of view drew the persecution of slaveholders in North Carolina and Levi and his family moved to Indiana from North Carolina in 1826.

While living in Indiana, Coffin would gain the financial strength to begin working on an array of business ventures designed to eliminate the societal dependence upon slave labor. While living in Indiana, Coffin quickly gained success as a local business leader, a merchant, and a farmer. After moving to Indiana, Coffin began to farm a tract of land. Within a year of his move he opened a general store.(10) During these business ventures Coffin used non-slave labor and managed to accumulate a great deal of wealth. Due to his success, Coffin believed that slavery could be abolished through breaking the financial dependence on slave labor. Coffin became a major investor in the Richmond branch of the Bank of Indiana. During his tenure as director during the 1830s, Coffin continued his efforts with the UGRR. One of his strategies for helping slaves took place within is bank dealings. In his biography Coffin describes an event where he assisted a man with financing the purchase of slaves in the south in order to have them emancipated in the north. Coffin assisted with transaction and led the man through the process.(11) His position in the banking and business community allowed him to finance the supply of food, clothing, and transportation for the UGRR operations in his region. His financial connections as bank director would allow Coffin to come into contact with many affluent abolitionists. He would use his position as bank director to carry out plans to assist slaves in finding freedom.

During these years, Coffin became aware of organizations in Philadelphia and New York City that only sold goods produced by free labor.(12) Known as the Eastern Free Produce Associations the organizations would finance Coffin in more free labor ventures. These free labor organizations desired to create similar endeavors in the western United States. The Salem Free Produce Association approached Coffin on several occasions, desiring for him to manage a proposed Western Free Produce Association. Coffin declined several times, citing lack of capital for investment and that he did not desire to move to Cincinnati.(13) In 1845 a group of abolitionist businessmen opened a wholesale mercantile business in Cincinnati.(14) The Free Produce Association raised $3,000 to assist with purchasing goods for the new warehouse.(15) The Free Produce Associations and supporting Quaker groups continued pressuring Coffin to take the position as the new association’s director. The Quaker groups claimed that there were no other western abolitionists qualified to manage the enterprise.(16) It is likely that there were no other candidates willing to govern such an endeavor because of the strong anti-abolitionist groups in the west. Reluctantly, Coffin accepted the position after being repeatedly induced to take it. However, Coffin stipulated that he would agree to the directorship only if he was able to oversee the warehouse for no more than five years. During that time, Coffin planned to train someone else to run the association.(17) From 1847 to 1857, Coffin continued the operation but was forced to abandon the project due to financial troubles. Coffin ran the enterprise often at his own out of pocket expense. The endeavor highlighted the faulty reasoning on which Coffin founded his thinking for free labor enterprises.

Part of the reason that Coffin’s original endeavors, in Indiana, were successful was due to the fact that he built a mill and began to produce linseed oil from flax he grew on his farm.(18) Thus Coffin controlled his own supply and quality of supply. The warehouse failed because Coffin could not find products that were cost effective to sell that were not made by slave labor. The failure of the warehouse could have been catastrophic, and was a terrible loss for Coffin. When it became apparent that the warehouse was failing, Coffin was unable to sell the business due to excessive losses. He was forced to close the warehouse and loss the investment along with many of his investors.

As well, Coffin’s general store was successful in spite of the fact that the community boycotted him for suspecting him of helping slaves.(19) The surrounding community was mostly proslavery although the growing abolitionist movement would eventually take control of the state. Indiana’s population was quickly growing and the majority of the new immigrants supported the anti-slavery movement. This influx of immigrants did not participate in the community boycott and Coffin’s business prospered. This was in reality a stroke of luck for Coffin because new immigrants needed work and did not support slavery since they saw slavery as negative factor for them in competing for jobs.(20) Still, this luck would not transfer to his warehouse business and other endeavors.

Undeterred by the failure, Coffin continued to create enterprises that tried to utilize free labor. Even during the 1840’s when pressure was increased on the Quaker communities that helped escaping slaves, Coffin still persisted in his legal endeavors to create a free labor business.(21) The Religious Society of Friends, the Quaker group to which Coffin attended advised all members to quit involvement in abolitionist societies and cease all assistance to runaway slaves. The Quakers had reversed their decision to oppose slavery through illegal means and decided that legal emancipation was the best course of action. It is important to understand that Quakers are deeply entrenched in abeyance of the law and found themselves torn between obedience to the law and the knowledge that slavery was immoral.(22)

Coffin was not able to comply with the group’s decision and continued assisting slaves. Even in the face of hostility from the surrounding community, Coffin still pushed forward in his aid to slaves. Coffin became the butt of threats from slave hunters and his friends pleaded with him to cease in his endeavors. Coffin in his biography would respond to the question of why he persisted in the face of danger,

After listening quietly to these counselors, I told them that I felt no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If by doing my duty and endeavoring to fulfill the injunctions of the Bible, I injured my business, then let my business go. As to my safety, my life was in the hands of my Divine Master, and I felt that I had his approval. I had no fear of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. If I was faithful to duty, and honest and industrious, I felt that I would be preserved, and that I could make enough to support my family.(23)

In 1843, Coffin was disowned from his Quaker group because of his refusal to take a passive role in fighting slavery. Coffin’s decision to go against the decision of his Quaker group was a major life altering decision. As a Quaker the group serves as unification of prayer and action. Obedience and unity to the group are considered spirituality in action and this was a driving force for Quakers with regard to antislavery activity. However, during this period the Quakers had a reversal in thought as a result of being torn between obedience to law and ideological opposition to slavery. The Quakers who had been fighting against slavery had decided that slavery must be fought through legislative means and not by breaking the law through abolitionist means.(24) For the Quakers, the rule of law seemed the best and most compatible means for achieving emancipation for blacks. For Coffin to go against his group shows a true conviction to the abolitionist movement. Coffin in response formed the Antislavery Friends Quaker group with likeminded individuals. This group and Coffin’s Quaker Friends Group would remain separated until 1851 when they were reunified.(25)

Coffin was able to maintain his support for the UGRR even when it seemed that many slave hunters and community members knew that he was involved. One must question how Levi was able to continue in the face of such opposition considering the fact that other abolitionists had been killed and jailed for assisting slaves. Slave hunters and federal marshals rounded up slaves and used force often in their pursuits of runaway slaves. Slave hunters and bounty hunters would pursue escaped slaves and took many liberties such as searching people’s homes and searching their wagons for hidden persons. Although the law did not authorize such activities slave hunters employed terroristic tactics such as threats against known slave sympathizers. Stories of violence against abolitionists and suspected abolitionists were quite common. In one instance, a farmer, Reuben Williams protested that slave hunters were unjustly searching his property and land. In retaliation the slave hunters beat the man.(26) The violence between escaped slaves and the slave hunters was also of great concern. Slave refugees new that they faced terrible punishments such as being whipped or having a foot amputated. In response to this fear refugees would lash out at slave hunters if given the opportunity.(27) Stories of this nature are common in the literature from this period and Coffin would have been aware of these horrors. The fact that Coffin was able to achieve this level of support without being outright attacked is a mystery.

The loss of Quaker support would not deter Coffin from continuing his efforts to establish business ventures, but this did not help his financial position either. The loss of Quaker support would make his business endeavors more difficult. Despite this opposition, Coffin and his wife Catherine organized a sewing society which produced clothing to give to the runaway slaves.(28) It should be noted that Catherine Coffin played an integral role in Coffin’s abolitionist dealings. Coffin mentions Catherine’s actions throughout his biography citing the gathering of clothing for slaves, providing care for those who were underfed, or sick. Catherine would be instrumental in providing support in the form of supplies. She would also work hand in hand with her husband during the war providing care to soldiers. She is also remembered for making toy dolls for slave children.(29)

In another act of luck, Coffin still had the support of many eastern abolitionists. They replaced some of aid that he lost because of his Quaker friends turning his back on him. Coffin was able to continue traveling and persisting in business endeavors without much stumbling because of the Quaker schism.

In an attempt to bolster the warehouse business, and to find a means of producing goods that was of equal quality to slave labor goods, Coffin traveled the south seeking a plantation that did not use slave labor. He met with limited success until he located a cotton plantation in Mississippi where the owner had freed all his slaves and operated by paying them as free laborers.(30) However, the plantation struggled financially because of lack of equipment to automate the cotton production. Coffin assisted the owner in the purchase of a cotton gin that greatly increased their productivity and provided a steady supply of cotton for his Western Free Produce Association. The cotton was shipped to Cincinnati where it was spun into cloth and sold.(31)

This endeavor was worthy of note for another reason in that it was at first successful but the quality of product that was produced was of equally poor quality of products produced by other free labor endeavors. There obviously existed some form of problem in that the free labor industries were incapable of producing quality products. One can only conjecture that blacks newly freed perhaps did not understand how to be an employee as opposed to being a slave and this most likely created a culture shock. After several generations of slavery, blacks were now lost in a world that did not accept them. Blacks who were newly freed had nothing and were still dependent on white people to provide for them in order to survive. More so, blacks although free were not in the truest sense free at all. It is not as though they had a wide array of choices available to them for career. It is quite possible that free blacks resented the work handed to them even by the well meaning Coffin.

As well, the cost for running the free labor facilities must have been considerably higher than slave industries since the products were made so cheaply and free of quality. This factor was probably the single worst enemy to free labor. In order to compete economically with slave plantations free labor associations and businesses would need to drive down prices as low as possible in order to afford to pay workers and this would mean using less expensive materials in the production process and therefore materials of lesser quality. Because the materials used in production were of low quality, this caused the creation of cheaply made products.

Coffin also took several trips to Tennessee and Virginia which were unsuccessful. His desire to create free labor business was severely hampered by the widespread use of slave labor in the south. The economics for a southern plantation or business to convert to free labor was almost impossible to make viable. It should be noted that slavery had created a system of market that was profitable, but only in the most classist sense. Large plantations made considerably more money than even merchants of the north but on the whole most southern planters had taken prices so low that they competed for just above breakeven wages.(32) This is one of the major problems that slavery created in that although overhead was low it reduced profit to the absolute lowest level. Coffin’s attempts to vie against this problem were futile because of the lack of profit already built into the slavery process. Therefore, planters and merchants in the south, even those who were against slavery, were not able to convert to free labor without risking their assets.

Coffin did succeed in sparking the interest of many people but was unable to procure more business ties.(33) Despite his intense commitment to the procurement and creation of free labor, the poor quality and cost of these products proved insurmountable.(34) Coffin often used trips of this nature to evangelize for the benefits of free labor. Coffin had considerable luck with changing individual viewpoints but could not seem to create a market or supply chain that suited his needs. However, Coffins advocacy roots would take place on many of these adventures and would lay the seeds for later aid to blacks after the war. For instance, many of these associations would help to form many different freedmen associations. This would provide necessary supplies and financial backing for assisting blacks with restarting their lives.(35) The personal ties that Coffin would create on these trips would also serve to propel him to positions of international political representation for the freedmen’s associations, after the war.

Coffin’s strategy for helping blacks changed radically as the Civil War began.(36) Coffin concentrated his efforts away from business and deeper into the UGRR activities and aid to help blacks become productive members of society. Coffin traveled to Canada in 1854 to visit the community of escaped slaves, many of them who he had assisted with escape. He assisted the community for several months and when he returned he created an orphanage in Cincinnati for blacks after having seen the number of slaves in Canada who were parentless.(37)

As the war began in 1861, Coffin and the Antislavery Friends Group began building up supplies intended to help the wounded. As a Quaker, Coffin was opposed to war, but he did support the war’s cause to free blacks and end slavery. During this time, Coffin, his wife, and many of his Quaker supporters spent almost every day working at Cincinnati’s war hospital caring for the wounded. Coffin’s conscientious objection to the war could be seen through his war aid. Coffin, his wife and their friends tended to southern soldiers equally to union soldiers. Coffin prepared and distributed food and coffee to these soldiers and personally gave shelter to soldiers in his home.(38)

Coffin was tireless as he still provided aid to newly freedmen out of his home and helped them find places to live. He somehow found time to assist these freedmen with education and clothing while at the same time serving the aid of soldiers. Coffin seemed to devote his existence to the abolition of slavery.

As Union soldiers pushed deeper into the South, some slaveholders murdered their slaves, while others abandoned them. This left countless slaves without food or shelter and displaced from their families. In response to this terrible problem, Coffin helped construct the Western Freedman’s Aid Society in 1863 to offer assistance to the slaves freed during the war. Coffin would continuously rely heavily upon his affluent abolitionist supporters and the ties he had made from his journeys to the south. His advocating and business adventures would pay off by providing the Society for donations to creating these groups. While Coffin himself donated unknown amounts of his own wealth into the abolitionist cause, without the support of his financiers, many of these endeavors would not have been possible. Using donations, Coffin and his group began collecting food and goods to be distributed to the former slaves.(39) Realizing the weight of this task, Coffin in conjunction with other newly formed freedmen associations, petitioned the government to create the Freedmen’s Bureau to offer assistance to freed slaves.

In 1863 President Lincoln was petitioned by several Freedmen Associations and Coffin was selected as one of the delegates to meet with Congressmen on the matter of forming the bureau. Coffin assisted with constructing the methods and logistics of how the aid would be provided to blacks. Coffin suggested geographic areas in which aid would be centralized.(40) Coffin’s counsel was well received and based on a solid understanding of where blacks were living. Coffin’s dealings in the Railroad would supply him with the understanding of where aid was most needed as blacks quickly began forming into isolated communities. Coffin was able to give important direction to the newly formed bureau whish allowed aid to be efficiently and effectively delivered.(41)

Coffin being a rather personal man did not care much for the public life. As a result, Coffin’s involvement in the Freedmen’s Bureau is somewhat muddled because he purposely did not bring attention to himself. It is known that he did help to instigate the formation of the Bureau, but a great deal of his involvement was in the providing of education to freedmen. Coffin realized that blacks would not be able to fend for themselves without proper education. Coffin seemed to prefer the hands on approach to working for the cause of freedmen and in his biography discusses his political dealings in a cursory manner but discusses in great deal his direct dealings with assisting people. For example, Coffin discusses at great length the distributing of supplies for freedmen.(42) This example highlights Coffins strengths and weaknesses. Although he was well liked, it would seem that Coffin lacked a certain aptitude or confidence for political maneuvering and as a result preferred his hands on approach. Coffin expressed this in his biography when he candidly states that, “…I felt that I was unequal to the task, and feared that I had mistaken my call to the work; I might make a failure in my attempt and injure the cause I had come to promote.”(43)

Coffin was also involved in helping freed slaves after the war in receiving educations.(44) Coffin would assist with providing education to blacks through various societies. He raised money for this endeavor through his overseas connections. As leader of the Western Freedman’s Aid society, he traveled to Great Britain in 1864 to seek aid.(45) His advocacy there led to the formation of the Englishman’s Freedmen’s Aid Society. Coffin had a great deal of skill in raising money and must have been very charismatic to have achieved the donation levels which he accomplished. The Englishmen’s Freedmen’s Aid Society provided clothing and money donations to assist blacks with rebuilding their lives.

In another instance, Coffin raised over $100,000 for the Western Freedman’s Aid Society to provide aid to the free blacks.(46) The society provided food, clothing, education, money, and other aid to the newly freed slave population in the United States. His advocacy extended to Paris when in 1867 he attended the International Anti-Slavery Conference in which British and other European representatives came together to discuss and provide assistance to slaves. This conference would raise money not just from the British but also from many other European powers.

Coffin personally did not like being in the public eye and considered advocating a demeaning position in which he was basically begging for money.(47) He expressed this in his biography that when a new leader was found for the position Coffin expressed that he was happy to step down from the position.(48) In contrast, Coffin had deep concerns about just giving money to blacks because he believed that many of these people would never be able to care for themselves without proper education and means of work. Although a deeply altruistic person, Coffin believed the society should only be sponsoring those blacks whom had the best chances of being able to benefit from the monetary sponsorship.(49) In this sense, Coffin becomes a realistic figure in history and not just a larger than life leader of slaves to freedom. Coffin recognized that the Society maintained limited resources and that many freed blacks would suffer.(50)

The Society continued to operate until 1870, the same year blacks were guaranteed equality in constitutional amendment. Sadly, the Society would end and without it would begin decades of prejudice and poverty for blacks. The quality of life for blacks would never improve much beyond what Coffin had accomplished for blacks until the civil rights movement in the 1960’s.

Coffin could never have predicted the struggle of Reconstruction and the decades of strife that blacks would be subjected to after Reconstruction. Knowing Coffin for the person he was through literature, he may very well have continued the Society had he known the future. One gets the sense that Coffin ends his career with a deserved satisfaction but also tired. When he had the opportunity to step down for his positions he did so quickly and without struggle. A lifetime of struggle with slavery seemed to tire the man.

After the war ended and the passage of the fourteenth amendment, Coffin lived his life in quiet retirement. Coffin stated in his biography that “…I resign my office and declare the operations of the Underground Railroad at an end.”(51) Levi Coffin died on September 16, 1877. Coffin’s attempt to secure business that was slave free was doomed for failure because of the economic and cultural difference in the prewar environment. Coffin did however; assist countless blacks to alter their lives after slavery. As a tireless advocate for human rights Levi Coffin was ahead of his time.

Coffin remains a hero in literature for his success in transporting slaves in the Underground Railroad. His success in sheer numbers surpassed the efforts of many of his more well-known counterparts such as Harriet Tubman. More importantly, Coffin’s efforts to assist blacks with education and cultural participation would endure long after his death. Although his efforts in the UGRR were amazing, having saved thousands of lives, his effort to improve the human condition for blacks is a part of history that seems to have been overshadowed by his participation in the Underground Railroad.

Coffin was in many ways an idealist and although his efforts at business failed to establish a market that was based on free labor, his efforts to include backs into the culture and workplace have been mostly ignored. On a smaller note, Coffin was also overlooked as a religious hero amongst Quakers around the world. His dedication to his faith served as beacon to Christian ideology. In an article published in the Christian Press, Coffin was described as a savior to those captured in the bondages of slavery.(52)

At the risk of his life and hazard to his family, Coffin fearlessly faced danger and the horrors of slavery. In his words concerning why he assisted runaway slaves, even in the face of peril, he said, “I thought it was always safe to do right.”(53)

Bibliography

Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin. Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876.

Bordewich, Fergus. Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad. New York: Amistad, 2006.

Morgans, James. John Todd And the Underground Railroad: Biography of an Iowa Abolitionist. Jefferson, N.C.: Tabor Historical Society and McFarland & Company, 2006.

Jordan, Ryan P. “The Dilemma of Quaker Pacifism in a Slaveholding Republic, 1833–1865.” Civil War History 53, no. 1 (2007): 5–28.

Newman, Richard S. The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Evans, Robert. The Economics of American Negro Slavery, 1830–1860. Washington D.C.: e National Bureau of Economic Research, 1962.

Yannessa, Mary Ann. Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana. Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001.

[1] Coffin is mentioned in Stowe, H.B. (1851/2). Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Specifically in Eliza and in Bound for Canaan by Fergus Bordewich New York: Amistad, 2006.

[2] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 1.

[3] Ibid., 3.

[4] Ibid., 3.

[5] Ibid.,, 3.

[6] Ibid., 5.

[7] Ibid., 4.

[8] Ibid., 7.

[9] Ibid., 12.

[10] Fergus Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad (New York: Amistad, 2006), 21.

[11] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 516–517.

[12] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 15.

[13] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 18.

[14] Ibid., 13.

[15] Fergus Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad (New York: Amistad, 2006), 23.

[16] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 107.

[17] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 15.

[18] Ibid., 10–11.

[19] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 32.

[20] Ibid., 14.

[21] Ibid., 16.

[22] Jordan, Ryan P. “The Dilemma of Quaker Pacifism in a Slaveholding Republic, 1833–1865.” Civil War History 53, no. 1 (2007): 5–28.

[23] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 187.

[24] Richard S. Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 32–34.

[25] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 16–17

[26] James Patrick Morgans, John Todd And the Underground Railroad: Biography of an Iowa Abolitionist (Jefferson, N.C.: Tabor Historical Society and McFarland & Company, 2006), 79–84.

[27] Ibid., 79–84

[28] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 19

[29] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 87.

[30] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 16–17

[31] Ibid., 26.

[32] Robert Evans, The Economics of American Negro Slavery, 1830–1860 (Washington D.C.: e National Bureau of Economic Research, 1962), 201–3.

[33] Jordan, Ryan P. “The Dilemma of Quaker Pacifism in a Slaveholding Republic, 1833–1865.” Civil War History 53, no. 1 (2007): 5–28.

[34] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 44.

[35] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 557.

[36] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 45.

[37] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 102.

[38] Ibid., 63.

[39] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 48.

[40] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 648–649.

[41] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 648–649.

[42] Ibid., 648–649.

[43] Ibid., 659.

[44] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 49.

[45] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 103.

[46] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 51.

[47] Ibid., 52.

[48] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 180.

[49] Ibid., 673.

[50] Mary Ann Yannessa, Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the Bonds of Slavery in Ohio and Indiana (Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 2001), 48.

[51] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Norman Oklahoma: R. Clarke & Co., 1876), 198.

[52] Ibid., 731.

[53] Ibid., 107.

~Citation~

Triola Vincent. Mon, Feb 01, 2021. Levi Coffin, the Underground Railroad, & Advocacy for Freedmen Retrieved from https://vincenttriola.com/blogs/ten-years-of-academic-writing/levi-coffin-the-underground-railroad-advocacy-for-freedmen